FRAMEWORKS- HOW TO BUILD ONE?

I am often asked what information security framework I use. Well, there are plenty to choose from. Many of them are excellent and some are even useful. New frameworks are developed quite often. Some are simply rebadging an old one, calling it “cyber”. Others have plenty of thought put into it and are quite valuable.

I am not prepared to argue here that Framework A is better than Framework B. I simply wish to call to your attention that the present situation, in short, is confused. This is a frustrating state of affairs and can present a problem, but the problem is not insurmountable.

As explained elsewhere, a framework provides guidance to the thought process, solving a problem. Not more, not less. It helps to ensure that most issues are dealt with; and dealt with thoroughly and systematically.

Dependent on the problem I try to solve, I might use different frameworks or elements of different frameworks. As I am getting more experienced, I tend to feel less need to follow someone else’s thought process. That is why I prefer to develop my own frameworks.

I should add that the remarks above are not intended to suggest that I am all knowing about frameworks. May it never be! The point I want to make is that asking my own questions is necessary to form my own thought processes. The result is to arrive at my own answers to what can be applied to the problem I am trying to solve.

All of this is said provisionally. I attempt to describe in the rest of this article the questions and methodology I use to create an information security framework. I am aware of course, that different solutions are generated by different questions. Therefore I put emphasis on the questions more than on the particular answers to those questions. I wish here only to show how these questions spiral into each other. Each reader must decide on their own answers and how to enact those answers.

Preliminaries

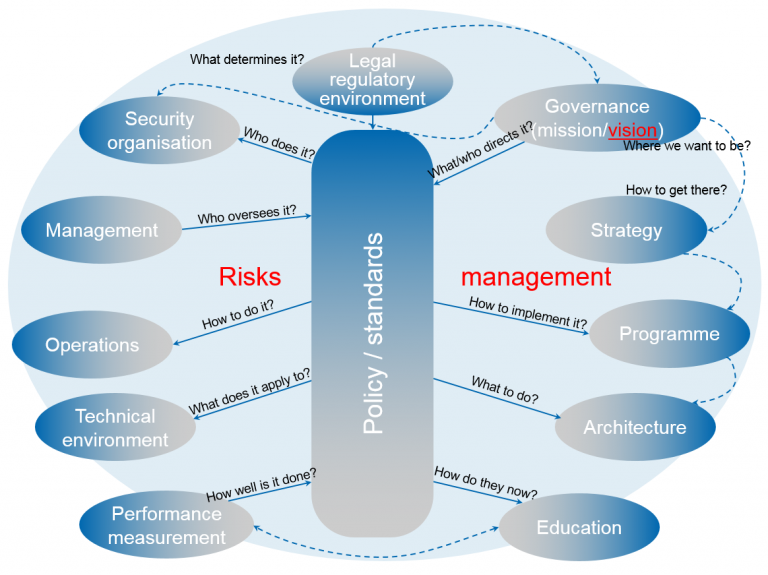

One might suggest that the core of an information security framework is a policy / standards set. All questions are flowing into or from it. Having said that, the policy / standard set must exist within the wider risk management environment of the organisation. A dedicated risk management framework detailing risk assessment, risk mitigation and contingency planning provides significant benefits once created separately.

The first question I ask is what determines the information security framework. I use this as a fitting starting point to examine the legal and regulatory environment of the jurisdiction in which my organisation operates. Creating a regulatory library is rather helpful to elucidate that. The other benefit is that during the process of creating the library, one can get reasonably familiar with the law of the land.

This is a matter of considerable importance, for it goes beyond the issue of compliance. Abiding – or not abiding – by the law of the land is a fundamental governance principle. Listing such principles is the initial input to the policy / standards set.

The starting point

This leads naturally to governing information security that answers the question of who or what directs it. Governance is not an elevated management function. It has performance roles, setting direction and compliance roles, establishing accountability. A separate framework is warranted here to work out the details properly.

Governance also deals with the intrinsic nature of the security organisation. “Who does the security work?” is the question to be asked. However, other questions need to be answered before one can address that question. Establishing clear mission and vision statements are essential here. Why does the security organisation exist? A mission statement – short and simple – answers that. Where do we – either as a whole or as a security organisation – want to be in a given period of time? A vision statement clarifies it.

These two statements – mission and vision – lead to information security strategy. “How do we get to where we want to be?” is the question. It is essential that the information security strategy is aligned to the overall business objectives. A separate framework is warranted here, too.

In addition to this and perhaps even more importantly, the order of asking these questions is of utmost importance. Having a strategy without clear mission and vision statements would make the whole information security framework unstable. Placing vision above mission has the same effect. If the organisation doesn’t know why it exists (self-identity), how can it define where it wants to be in the future? If it doesn’t know where it is heading, how can it get there? The danger of starting on a journey for which there is no destination is looming in the not too far distance. It might seem pedantic to some, but getting governance right is essential for a robust information security framework.

First things first

It is reasonable to argue that strategy and policy are not directly connected to each other. Strategy is the means by which an organisation defines where it is headed and why. An information security policy is a statement of intent by management on the basic rules; linking legal and business requirements with security controls. One doesn’t have a direct input into the other. They can be aligned, but what I am at pain to emphasise is that they exist concurrently, yet independently.

The outcome of a well-developed information security strategy is an information security programme, delivering benefits, not individual outcomes. Such a programme provides a macro view of the information security work, answering the question of how pro-active, strategic change can be implemented. Common strategic goals are worked out and the discipline and techniques for the necessary work is provided.

As the programme furnishes the necessary implementation environment, the question of what actually has to be done, arises. Information security architecture answers this question. A conceptual architecture produces a cohesive design that addresses the security requirements flowing from the policy and standards.

The work – Operations

As I remarked earlier, these are precursory questions for the information security organisation, leading to answer who does the security work. Allocation of information security accountabilities, decision making rights and responsibilities to perform information security related processes ensure that the roles and expectations are clear. And there is one other point to be made. A person may fulfil a role which coincides with their job title, yet role names should not be confused with job titles. Equally important is that all identified tasks are executed by a role.

The next logical question then that needs to be answered is: who assigns those roles and who oversees the work defined in the conceptual architecture. Establishing the security management function ensures that the command hierarchy along which instructions are passed on is clear.

I have previously referred to the difference between governance and management. The two should not be mixed. Perhaps I can get a bit closer to the point with a metaphor. While there are elements of directing and controlling in management, the major difference between governance and management – to put it simply – is that management is a hands-on activity. Governance in contrast should not get involved in day-to-day operations. A transition from hands-off to hands-on activities needs to happen to enable smooth operations.

Operations addresses the question of how to do the work. Business and development processes need to be refined and calibrated to efficiently integrate security processes. Infusing information security methods and related activities transparently into every business activity sets a practical base to approach information security.

Implicit in expressing this idea is the concept of security by design. Some might consider it only as a software development concept. I prefer to extend it to each and every business activity. The principal argument is – to be clear on this point – that information security should not be an afterthought or an add-on, but integral to everything a business does.

Understanding operations from both sides – business and information security – is therefore a necessity. Each side needs to be clear on what the other needs. Business needs to be aware of the information security requirements not just to preserve value, but also to create value. Information security professionals need to understand what the business needs and how they can contribute to it. Therefore, information security professionals should be encouraged to acquire new skills while honing existing ones. Knowledge should be shared without fear of losing relevance. A combination of breadth of coverage and depth of knowledge is ideal.

Building the controls

The next question leads to considering the technical environment. Security requirements need to be captured as they emerge. The controls identified in the information security standards need to be applied and built into the technical environment. The question of “what those controls are applied to?”, is answered in technical architecture. A defense-in-depth architecture built on trust zones represents a wise choice of many alternatives.

Using an international standard or framework in my experience is most useful for control development. I aim to combine elements of knowledge from more than one discipline here as it enables me to address cross-functional business risks. Control effectiveness is another important consideration. This is not just the level of protection they provide, but also the cost effectiveness. The organisation’s risk appetite can play a role here.

Controls also need to be categorised very carefully. Even if they work as intended, each individual control has its limitations. They can even introduce new risks, therefore considering compensation for those limitations is essential.

Another aspect is to consider the most appropriate controls along the breach event timeline. Each control targets different stages of the breach timeline and is applied differently. It ties back to effectiveness mentioned earlier.

The six control categories I use are: deterrent, detective, preventive, compensating, corrective and recovery controls. All six can be categorised further into managerial/administrative, operational, technical/logical and physical controls. A good approach to this categorisation might be to create a matrix; listing the first set on the horizontal axis, the second set on the vertical axis.

Assurance

Operational integrity is achieved when security practices and control architectures for business operating models are constantly evaluated and improved. This goes beyond assessing control effectiveness. The benefits, a given control would produce are important to consider as well. Ultimately, one needs to ensure not only that the right controls, but also the most appropriate risk treatments are selected.

The information security culture including people’s behaviour can enhance or break the information security posture of the organisation. People, who access information and information systems, need to understand the importance and the level of information security applied by those controls. “How do they know this?”, is the question. A well designed information security education framework would address that.

Such a framework would allow for the learning continuum, distinguishing between awareness, training and education. Each targets different audience, therefore adult learning has to be considered along with the collective and individual needs of the learners. The targeted level of security knowledge can be fine-tuned by using a training matrix. Structuring the education into phases and campaigns; including complimentary artefacts that enhance the learning process are just as important as the actual body of knowledge, the teaching objectives, the teaching methods and the purpose of measurement.

Finally, the question of how well the information security work is done, or more colloquially, “is everything OK?” should be considered. Measurements, including performance indicators need to be established to allow management to monitor and evaluate effectiveness and efficiency of information security. Such KPIs might include return on security investment (ROSI), SLAs, individual and system performance targets.

The outline established

This is the introductory part of the work. I find it necessary, for the purpose of clarifying our present situation and indicating what dangers lie ahead, to quickly recap the basic questions to be asked:

What determines the framework?

What/who directs it?

Who does it?

Who we are and where do we want to be?

How to get there?

How to implement the framework?

What to do?

Who oversees it?

How to do it?

What does it apply to?

How well is it done?

How do they know it?

I use the questions asked as the glue that holds the individual elements together. These are, in my view, extremely useful questions although, agreeably, not the only ones that can be asked. As an additional aid, below is a diagram to show the conceptual framework created by these questions.

Questions, one might say, are the principal intellectual instruments available to human beings; therefore asking them is a necessity. These questions and dozens more like them are the means through which it might be possible to generate knowledge leading to new facts, new perspectives, and new ideas. I didn’t provide answers, because it is not important that those who ask the questions arrive at my answers.

This is by no means an original idea, and it would be foolish to deny that there were not certain problems attending this whole adventure. I am well aware that this approach might be peculiar to some. Equally plausible approaches can be developed. The key to success in my view though is to learn how to ask insightful and penetrating questions.

Building up the framework

Once the outline is established and is stable, I use an approach I named as the “Four keys”. I record for each area established the key objective, key considerations, key components and the key participants. Starting with the key objective should be mandatory; however the other three can be addressed in a random order. It is possible, if not recommended, that key considerations and key components should be developed simultaneously; moving frequently between the two. Each can feed into the development of the other.

The key objective links the other three “keys” to the question asked that established the given framework element. In saying this, I do mean to ensure that the key objective answers the area’s question with clarity and simplicity. Having a clear chain of command can be for example the objective to the management element.

Key considerations are useful to ensure that nothing is overlooked or omitted. The principles of management[1] and organisational economics[2] for example would be natural candidates for inclusion in the management element. Key considerations are not prescribed texts, only pointers. The level of details is up to the framework creator.

The key components section lists the artefacts required. Roles and responsibilities; operational plan and budget, specific to information security would be such items for the management element. Artefacts identified but not yet existing would need to be developed. One might note that the effort required to do so can be significant. This however belongs to implementation, not to the creation of the framework.

The development of key components would benefit most from using other frameworks. The artefacts can be considered as controls, so international standards and specific information security frameworks are useful to check against what the developer believes is a necessary component. Comparing these frameworks not just for what they include but also what each one omits can also be illuminating.

The last key to be worked out is the key participants for each “key”. As a general rule, the framework owner and the person responsible for a particular area of work are always included. Key considerations in my experience would need to involve members one level up on the organisational hierarchy, while members from one level down or even external parties would be participants in developing the key components.

The picture below illustrates how the “Four keys” fit together.

Final remarks

As I indicated at the start, I have tried to show how the elements of an information security framework can be built. Here I wish to conclude by making two observations, both of which I have already stated but which bear repeating. The first is that different solutions are generated by different questions. Second, that those solutions might be equally plausible.

I would not hesitate to go so far as to say though that the solutions we carry in our heads are largely meaningless unless we know the questions which produced them. The questions we select to ask determine where and how we look for answers. This would define the extent of available choices. Consequently, the way we form our questions determines the kind of answer we decide to get from the available choices.

I do not imagine I have said anything original. I wanted merely to affirm the importance of asking appropriate questions. All of these may seem obvious enough, yet many seem to ignore the questioning process altogether. Here I offered my own thought and question processes, hoping that some might find them useful. As stated in my introductory remarks I intended this to be an impetus to inquiry, – not a conclusion. Don’t take and copy my approach, only the concept of asking questions. Attending to it is its own reward.

EB 2018 Feb